The Bubonic Plague, also known as the Black Death, was one of the deadliest pandemics in human history. It had a profound impact on society, causing widespread fear, social upheaval, and demographic shifts. This devastating disease left an indelible mark on the world, forever changing the course of history.

The first recorded outbreak of the Bubonic Plague occurred in the 6th century, during the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian, around 542 AD. This early outbreak, known as the Plague of Justinian, swept through the Byzantine Empire and had a significant impact on the economy and social structure of the time. It is estimated to have killed millions of people and contributed to the decline of the empire.

In the 14th century, the Bubonic Plague swept across Europe, resulting in the most devastating outbreak. It is estimated to have killed 25 million people, or about one-third of Europe’s population at the time. This catastrophic event, known as the Black Death, led to widespread death and suffering, as entire communities were decimated by the disease. The impact of the Black Death on Europe’s population and society was unparalleled.

The Bubonic Plague is caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis, which is typically transmitted through fleas that infest rats. These fleas would bite infected rats and then bite humans, spreading the bacteria. The high population density of rats in cities, combined with poor sanitation practices, provided ideal conditions for the transmission of the disease.

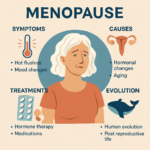

The most common symptoms of the Bubonic Plague include fever, chills, weakness, swollen and painful lymph nodes (called buboes), and gangrene. The appearance of buboes was a distinctive characteristic of the disease and gave it its name. The swelling and pain caused by the buboes were often excruciating, and the disease progressed rapidly, leading to severe illness and death in many cases.

The Bubonic Plague was named after the distinctive black patches that appeared on the skin of infected individuals, caused by internal bleeding. This discoloration was a result of blood vessels bursting due to the systemic effects of the disease. The appearance of these dark patches further heightened the terror and despair associated with the plague.

During the initial outbreaks, mortality rates were extremely high, ranging from 30% to 90%. The severity of the disease and its rapid spread contributed to the staggering number of deaths. The lack of effective treatment and understanding of the disease meant that many infected individuals had little chance of survival.

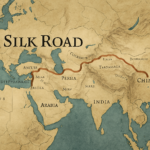

The Bubonic Plague is believed to have originated in Central Asia and spread to Europe along trade routes such as the Silk Road. Merchants and travelers unknowingly carried infected fleas and rats, introducing the disease to new regions. The interconnectedness of trade networks played a significant role in the global dissemination of the plague.

The first major outbreak in Europe occurred in 1347 when ships from the Black Sea port of Caffa (now Feodosia, Ukraine) arrived in Sicily with infected sailors. It is said that the besieged city of Caffa catapulted infected corpses over its walls, unknowingly spreading the disease to the attacking forces. The Italian merchants who fled from Caffa to Italy carried the disease with them, initiating one of the most devastating pandemics in history.

The pandemic spread rapidly throughout Europe, with notable outbreaks occurring in cities like Florence, Venice, and Paris. As population centers with bustling trade and dense urban environments, these cities were particularly vulnerable to the spread of disease. The arrival of infected individuals in these major centers acted as a catalyst for the spread of the Bubonic Plague, resulting in widespread devastation and loss of life.

The Bubonic Plague also reached England, and the first recorded outbreak in London took place in 1348. The disease rapidly spread throughout the city, causing immense panic and leading to a staggering number of fatalities. The crowded and unsanitary conditions of medieval London exacerbated the transmission of the disease, making it a hotbed for the spread of the plague.

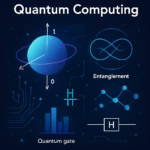

The bacterium Yersinia pestis was identified as the cause of the Bubonic Plague in 1894 by Alexandre Yersin, a Swiss-French physician. Yersin conducted groundbreaking research that allowed for a better understanding of the transmission and nature of the disease. His discovery played a crucial role in subsequent efforts to control and combat the plague.

In some instances, entire villages and towns were completely wiped out by the plague. The devastation caused by the Bubonic Plague was so immense that it left deserted settlements and ghost towns in its wake. Communities that were once thriving and vibrant became haunting reminders of the catastrophic impact of the disease.

During the outbreaks, mass graves called plague pits were used to bury large numbers of victims. Due to the overwhelming number of deaths, traditional burial practices were insufficient. Plague pits allowed for the swift disposal of bodies, preventing further spread of the disease and minimizing the risk of contamination.

The peak of the Bubonic Plague in Europe lasted from 1347 to 1351. This period witnessed the most significant impact of the disease, with millions of people succumbing to its deadly grip. The rapid spread of the plague and its devastating consequences forever altered the social, economic, and cultural landscapes of Europe.

The Bubonic Plague affected not only Europe but also other parts of the world, including Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. The disease made its way across continents through trade routes and travel, wreaking havoc on diverse societies and leaving a global legacy of suffering and death.

The death toll from the Bubonic Plague in Europe alone is estimated to be between 75 and 200 million people. Such massive loss of life led to a significant reduction in the population, causing long-lasting demographic shifts and a subsequent impact on various aspects of European society.

In the 19th century, the Bubonic Plague resurfaced periodically, causing outbreaks such as the Third Pandemic, which originated in China in the 1850s and spread globally. This epidemic marked a resurgence of the disease and posed significant challenges to public health systems and medical advancements of the time.

In the 20th century, advances in medical knowledge and antibiotics helped to control and treat the Bubonic Plague more effectively. Streptomycin, an antibiotic discovered in 1943, proved to be particularly effective in combating the disease. These medical advancements led to a considerable decrease in the mortality rate associated with the plague.

The World Health Organization (WHO) considers the Bubonic Plague as a re-emerging disease and monitors its occurrences worldwide. Although the disease is no longer at pandemic levels, sporadic cases still occur, primarily in regions with poor sanitation and inadequate healthcare infrastructure. Vigilance and swift response measures are crucial in preventing outbreaks and the potential for further spread.

The last major outbreak of the Bubonic Plague was in 1920-1926 in China, which resulted in around 12 million deaths. This epidemic marked a significant event in the history of the disease, showing that despite improved medical knowledge, the Bubonic Plague could still cause considerable devastation if left unchecked.

The Bubonic Plague has influenced art, literature, and culture throughout history, with notable references in works like “The Decameron” by Giovanni Boccaccio. Artists, writers, and thinkers found inspiration in the grim reality of the plague, addressing its horrors, mortality, and the reflection of society in the face of such immense suffering.

The development of quarantine practices and public health measures can be traced back to the response to the Bubonic Plague outbreaks. The need to contain and prevent the spread of the disease led to the establishment of isolation practices, such as quarantining ships and individuals, which had a lasting impact on modern public health protocols.

The term “quarantine” was derived from the Italian word “quaranta giorni,” meaning “forty days,” which was the period ships had to stay isolated to prevent the spread of the disease. The concept of a specific isolation period has its roots in the measures implemented during the Bubonic Plague outbreaks, highlighting the historical significance of the term.

Modern research on the Bubonic Plague has led to a better understanding of its biology, transmission, and methods of prevention. Scientists have made significant progress in studying the genetic makeup of Yersinia pestis and identifying factors that contribute to its virulence. Additionally, public health organizations maintain surveillance systems and response mechanisms to prevent potential outbreaks and mitigate the impact of the disease.