Chickenpox is a highly contagious viral infection caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). It was once considered an almost inevitable childhood illness, but the introduction of the varicella vaccine in the mid-1990s has significantly reduced its prevalence. Despite the decrease in cases due to vaccination, chickenpox remains a relevant public health topic because of its potential complications and the connection to shingles later in life. Here are some interesting and verified facts about chickenpox, its impact, and the measures taken to prevent it.

Virus: Chickenpox is caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), a member of the herpes virus family, known for causing both varicella (chickenpox) and herpes zoster (shingles). The varicella-zoster virus is a double-stranded DNA virus that is highly contagious, easily spreading from person to person. The virus enters the body through the respiratory system or direct contact with an infected person’s rash, quickly establishing an infection. After initial exposure, VZV travels through the bloodstream to the skin, where it causes the characteristic rash associated with chickenpox. Following the resolution of chickenpox, VZV can remain dormant in nerve cells for many years, potentially reactivating later in life as shingles.

Incubation Period: The incubation period for chickenpox typically ranges from 14 to 16 days after initial exposure to the varicella-zoster virus, although it can be as short as 10 days or as long as 21 days. During this period, the virus is multiplying in the body but has not yet caused symptoms. This time frame is crucial for the spread of the virus because an infected person can unknowingly transmit the virus to others before symptoms appear. Understanding the incubation period helps in diagnosing chickenpox and implementing preventive measures to control outbreaks, especially in environments like schools or daycare centers where the virus can spread rapidly.

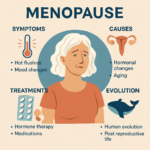

Symptoms: The initial symptoms of chickenpox are often mild and can include fever, fatigue, and loss of appetite, which occur before the distinctive rash appears. These early symptoms, known as the prodromal phase, are typically followed by the development of a highly itchy rash that progresses in stages. The rash usually starts on the chest, back, and face before spreading to other parts of the body, including the scalp, mouth, and even the eyes. In some cases, chickenpox can also cause mild flu-like symptoms such as headaches, body aches, and a general feeling of discomfort. The severity of symptoms can vary widely from person to person, with children often experiencing milder symptoms than adults.

Rash Development: The chickenpox rash develops in three distinct stages over the course of several days. The first stage involves the appearance of raised red bumps, known as papules, which can appear anywhere on the body. These bumps then progress to the second stage, where they become fluid-filled blisters, or vesicles. Finally, in the third stage, the blisters break open and form crusts or scabs as they begin to heal. New bumps continue to appear for several days, resulting in a mixture of stages on the skin at any given time. This progression from bumps to blisters to scabs is a hallmark of chickenpox and is a key feature used by healthcare providers to diagnose the infection.

Contagiousness: Chickenpox is highly contagious and can spread easily from person to person through respiratory droplets released when an infected person coughs or sneezes. It can also spread through direct contact with the fluid from chickenpox blisters. The virus is most contagious from 1 to 2 days before the rash appears until all blisters have formed scabs, typically about 5 to 7 days after the rash first develops. Because chickenpox is so contagious, it can quickly spread through households, schools, and communities, especially among individuals who have not been vaccinated or have never had the disease.

Prevalence: Before the introduction of the varicella vaccine in 1995, chickenpox was extremely common, with nearly all children contracting the disease by age 15. It was considered a rite of passage for childhood, with most cases occurring in children between the ages of 5 and 9. Outbreaks were frequent, especially in schools and daycare centers where the virus could easily spread among unvaccinated children. In the pre-vaccine era, chickenpox was a leading cause of morbidity among children, causing numerous hospitalizations and some deaths each year in the United States and around the world.

Vaccination: The varicella vaccine was first licensed in the United States in 1995 and has had a significant impact on public health by greatly reducing the incidence of chickenpox. The vaccine, known as Varivax, contains a live, attenuated (weakened) form of the varicella-zoster virus, which stimulates the immune system to develop immunity without causing the full-blown disease. Following the introduction of the vaccine, chickenpox cases, hospitalizations, and deaths have all declined dramatically. The widespread use of the varicella vaccine has made chickenpox much less common in countries with high vaccination rates, illustrating the vaccine’s effectiveness in controlling this once-ubiquitous childhood illness.

Vaccine Efficacy: The varicella vaccine is about 90% effective in preventing chickenpox infection and is 100% effective against severe forms of the disease. This means that while some vaccinated individuals may still contract chickenpox, these breakthrough cases are typically mild and involve fewer lesions, shorter duration, and reduced risk of complications. The vaccine’s high efficacy has played a crucial role in reducing the overall burden of chickenpox in vaccinated populations, leading to fewer hospitalizations, complications, and deaths associated with the virus. Furthermore, vaccinated individuals who do contract chickenpox are less likely to spread the virus to others, contributing to herd immunity and protecting those who cannot be vaccinated.

Complications: Complications from chickenpox, although rare, can be severe, particularly in certain populations such as infants, adults, pregnant women, and individuals with weakened immune systems. Common complications include bacterial infections of the skin, pneumonia, and encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain. Secondary bacterial infections can occur when bacteria enter the skin through broken blisters, leading to conditions such as impetigo or cellulitis. Pneumonia, a lung infection, can develop if the virus spreads to the respiratory system, and encephalitis can cause serious neurological symptoms and even be life-threatening. These potential complications underscore the importance of vaccination to prevent chickenpox, especially in vulnerable groups.

Death Rate: Prior to the introduction of the varicella vaccine, chickenpox caused approximately 100 deaths per year in the United States alone. Most of these deaths occurred in previously healthy children and adults who developed severe complications from the infection. The high death rate associated with chickenpox highlights the potential seriousness of the disease, even though it is often perceived as a mild childhood illness. Since the vaccine’s introduction, the number of deaths due to chickenpox has dramatically decreased, underscoring the vaccine’s effectiveness in preventing severe disease and saving lives. The dramatic reduction in mortality also reflects broader public health benefits, including decreased hospitalizations and healthcare costs associated with chickenpox complications.

Shingles Connection: The varicella-zoster virus (VZV), the same virus that causes chickenpox, can remain dormant in the body’s nerve cells for years after the initial infection. This latent virus can reactivate later in life, particularly in older adults or those with weakened immune systems, causing shingles, also known as herpes zoster. Shingles is characterized by a painful rash, often localized to one side of the body, along a nerve pathway. The rash can lead to severe pain, itching, and even complications such as postherpetic neuralgia, a condition where pain persists long after the rash has healed. The connection between chickenpox and shingles highlights the long-term implications of VZV infection, making vaccination against chickenpox important not only to prevent the initial illness but also to reduce the risk of shingles later in life.

Age Factor: Chickenpox tends to be more severe in adults than in children. While the disease is generally mild in most healthy children, adults who contract chickenpox are more likely to experience severe symptoms and complications, such as pneumonia, hepatitis, and encephalitis. The increased severity in adults may be due to the immune system’s heightened inflammatory response to the virus. In addition, adults are more likely to develop a higher number of lesions and experience a longer duration of fever and malaise. Pregnant women are particularly at risk, as chickenpox can lead to serious complications for both the mother and the developing fetus, including congenital varicella syndrome. This age-related severity underscores the importance of vaccination for adults who have not previously been exposed to the virus.

Global Impact: Chickenpox remains common in many parts of the world, especially in countries where varicella vaccination programs are not widely implemented or accessible. In these regions, chickenpox continues to be a leading cause of childhood illness, resulting in significant morbidity and, in some cases, mortality. In tropical climates, chickenpox can occur throughout the year, whereas in temperate regions, it often shows a seasonal peak in the late winter and early spring. The lack of vaccination programs in some countries means that the virus can easily spread, causing outbreaks in communities and increasing the burden on healthcare systems. Global efforts to expand vaccination coverage are crucial to reducing the incidence of chickenpox and preventing severe complications associated with the disease.

Historical Records: The first recorded description of chickenpox dates back to the 17th century by the English physician Richard Morton. In 1694, Morton distinguished chickenpox from smallpox, a more severe disease caused by the variola virus. His observations laid the groundwork for understanding chickenpox as a distinct illness, separate from other pox-like diseases. The name “chickenpox” itself is thought to have originated from the blisters’ appearance, which were said to look like chickpeas or were considered a “weaker” form of pox compared to smallpox. Over time, further medical observations and advances have improved the understanding of chickenpox, leading to the development of effective treatments and preventive measures, such as the varicella vaccine.

Rash Duration: The chickenpox rash typically lasts about 5 to 7 days. It begins as small, red, itchy bumps that quickly progress to fluid-filled blisters. Over time, these blisters burst and form scabs, which eventually fall off as the skin heals. The rash usually appears in waves, with new lesions forming for several days after the initial outbreak. This means that an individual can have all three stages of the rash—red bumps, blisters, and scabs—present at the same time. The duration of the rash can vary depending on the severity of the infection and the individual’s immune response. During this period, the affected person remains contagious, and it is important to avoid contact with others, especially those who are unvaccinated or immunocompromised.

Lesion Count: An individual infected with chickenpox can develop between 250 to 500 itchy blisters during an outbreak. The number of blisters varies depending on the severity of the infection and the person’s immune response. In some cases, individuals may develop fewer lesions, while others may experience a more extensive rash covering most of the body. The blisters tend to be most concentrated on the chest, back, and face but can also appear on the scalp, inside the mouth, and even in the genital area. Scratching the blisters can lead to bacterial infections and scarring, so it is important to manage the itchiness with appropriate treatments, such as antihistamines and soothing lotions, and to keep fingernails trimmed and clean.

Immunity: After recovering from chickenpox, most individuals develop lifelong immunity to the virus, meaning they are unlikely to contract chickenpox again. This immunity occurs because the body’s immune system produces specific antibodies that recognize and fight off the varicella-zoster virus if it is encountered again. However, the virus remains dormant in the body’s nerve cells and can reactivate later in life as shingles, particularly in individuals with weakened immune systems or those undergoing stress. While rare, some people may experience a second bout of chickenpox if their initial infection was very mild or if their immune system is significantly compromised.

Zoster Vaccine: A vaccine for shingles, called the zoster vaccine, was approved for use in the U.S. in 2006. The zoster vaccine is designed to boost the immune system’s response to the varicella-zoster virus, reducing the risk of shingles and its associated complications, such as postherpetic neuralgia. There are two types of shingles vaccines: Zostavax, a live attenuated vaccine, and Shingrix, a recombinant vaccine. Shingrix, approved by the FDA in 2017, is recommended for adults aged 50 and older and has been shown to be more than 90% effective in preventing shingles. Vaccination is particularly important for older adults, as the risk of developing shingles increases with age.

Transmission Period: An individual infected with chickenpox can spread the virus from 1 to 2 days before the rash appears until all blisters have crusted over, which usually takes about 5 to 7 days after the rash first develops. During this period, the infected person is highly contagious, and the virus can be transmitted through respiratory droplets or direct contact with the fluid from the blisters. The ability to spread the virus before the appearance of the rash makes it difficult to control outbreaks, as individuals may unknowingly infect others before realizing they are sick. Preventive measures, such as vaccination and isolation of infected individuals, are crucial in reducing the spread of chickenpox.

Global Vaccination Rates: As of 2020, about 85% of children in the U.S. received the varicella vaccine by age 2. This high vaccination rate has led to a significant decrease in the incidence of chickenpox in the United States, resulting in fewer cases, hospitalizations, and deaths associated with the virus. The widespread adoption of the varicella vaccine has also contributed to herd immunity, protecting those who cannot be vaccinated due to medical reasons. However, vaccination rates can vary by region and community, and efforts to increase coverage are essential to ensure the continued success of chickenpox prevention programs. Global vaccination rates are lower in many other parts of the world, highlighting the need for increased access to vaccines and education about their benefits.

Cost of Vaccination: The cost of the varicella vaccine in the United States is approximately $150 per dose. This cost can vary depending on factors such as location, healthcare provider, and insurance coverage. The vaccine is typically administered in two doses, meaning the total cost for complete vaccination can be around $300 without insurance. However, many health insurance plans cover the cost of childhood vaccinations, including the varicella vaccine, which can significantly reduce or eliminate the out-of-pocket expenses for families. Public health programs, such as the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program, also provide vaccines at no cost to eligible children in the United States, ensuring that cost is not a barrier to protecting against chickenpox.

Vaccine Schedule: The varicella vaccine is typically administered in two doses to provide optimal protection against chickenpox. The first dose is given to children between 12-15 months of age, and the second dose is administered between 4-6 years of age. This two-dose schedule was established after studies showed that a single dose was not always sufficient to prevent chickenpox outbreaks. The second dose helps to ensure long-lasting immunity and reduces the likelihood of breakthrough infections, where a vaccinated person still contracts a mild form of chickenpox. Following this recommended vaccination schedule is important for maintaining high levels of immunity within the community and preventing the spread of chickenpox.

Immunocompromised Risks: Individuals with weakened immune systems are at a higher risk of severe complications from chickenpox. This group includes people with conditions such as HIV/AIDS, cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressive drugs, and those taking long-term steroids. In these individuals, chickenpox can lead to serious complications, including severe skin infections, pneumonia, hepatitis, and encephalitis. Because of their increased vulnerability, immunocompromised individuals are often advised to avoid contact with anyone who has chickenpox or has been recently vaccinated with the live varicella vaccine, which could potentially spread the virus in rare cases. Preventive strategies, such as antiviral medications and varicella-zoster immune globulin (VZIG), are sometimes used to protect those at high risk.

Chickenpox Parties: Before the widespread availability of the varicella vaccine, some parents held “chickenpox parties” to intentionally expose their children to the virus. The idea behind these gatherings was to ensure that children contracted chickenpox at a young age when the disease is generally milder and less likely to result in complications. Parents believed that natural infection would provide lifelong immunity, thus avoiding the risk of a more severe infection in adulthood. However, with the development and availability of the varicella vaccine, which provides safe and effective immunity without the risks associated with natural infection, chickenpox parties are no longer recommended. Deliberately exposing children to the virus can lead to unnecessary illness, potential complications, and the spread of the virus to vulnerable individuals.

Public Health Impact: The introduction of the varicella vaccine has led to a 90% decrease in chickenpox cases in vaccinated populations. This significant reduction in cases has also resulted in a corresponding decline in hospitalizations, complications, and deaths associated with the virus. The vaccine has been highly effective in preventing both mild and severe forms of chickenpox, contributing to overall public health and reducing the economic burden of the disease on healthcare systems. Herd immunity, achieved through high vaccination rates, protects individuals who cannot be vaccinated, such as infants and those with certain medical conditions. The success of the varicella vaccine highlights the importance of vaccination programs in controlling infectious diseases and protecting community health.

Frequently Asked Questions About Chickenpox

What is chickenpox?

Chickenpox, also known as varicella, is a contagious viral infection that causes an itchy rash and fever. It is caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV).

What are the symptoms of chickenpox?

The symptoms of chickenpox typically appear 10 to 21 days after exposure to the virus. They may include:

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Headache

- Loss of appetite

- An itchy rash that starts as small, red bumps and develops into fluid-filled blisters. The rash typically appears on the face, chest, back, and limbs.

How is chickenpox spread?

Chickenpox is highly contagious and can spread through direct contact with the rash, airborne droplets, or contact with contaminated objects.

Who is at risk for chickenpox?

Anyone who has not been vaccinated against chickenpox or had the disease is at risk. However, infants, pregnant women, and people with weakened immune systems are at a higher risk for complications.

What are the complications of chickenpox?

While most cases of chickenpox are mild, complications can occur, especially in infants, pregnant women, and people with weakened immune systems. These complications may include:

- Secondary bacterial infections

- Pneumonia

- Encephalitis

- Shingles (a painful, blistering rash that can develop in adults who have had chickenpox)

How is chickenpox treated?

There is no specific treatment for chickenpox. However, over-the-counter pain relievers can help relieve fever and discomfort. Cool baths or oatmeal baths can also help soothe the itchy rash.

Can chickenpox be prevented?

Yes, chickenpox can be prevented through vaccination. The chickenpox vaccine is safe and effective and can be given to children as young as 12 months old. Adults who have not had chickenpox or the vaccine can also get vaccinated.

How long is a person with chickenpox contagious?

A person with chickenpox is contagious for about a week, or until the rash has crusted over.

Should a person with chickenpox stay home from school or work?

Yes, a person with chickenpox should stay home from school or work until the rash has crusted over to prevent spreading the virus to others.